As we begin our day of deliberations and discussion, let us all be aware this morning that the Lora Lake 8 – those mostly homeless individuals who were arrested in the course of occupying the Lora Lake Apartments in Burien – have a court hearing, which was scheduled for 8:45 am. Hopefully they will be joining us here soon. Let us give them a warm welcome and demonstration of our appreciation when they arrive.

Allow me to preface my speech by stating that what I have to say may be somewhat unsettling. I plan to be here for the entire day and I will be happy to discuss any portion of my talk with anyone.

Once, the great Irish writer James Joyce was asked why he wrote so often about Dublin, Ireland, the city of his birth. In his early adulthood, Joyce had left Dublin and Ireland and would never return. To the question, Joyce responded that in the particular he saw the universal. I will begin my talk starting with more universal issues and end with some immediate particulars pertinent to our locality.

“The Time of the End Is the Time of No Room” is the title of an essay by the great Trappist monk Thomas Merton (The essay appears in the book “Raids On the Unspeakable”, 1966). Therein he assesses our apocalyptic time, one “haunted by the demon of emptiness” out of which come “the armies, the missiles, the weapons, the bombs, the concentration camps, the race riots, the racist murders, and all the other crimes of mass society.” If Merton were alive today, he would add to the sordid list the teeming masses of dispossessed homeless and impoverished within our misguided and opulent society.

Merton asks: “Is this pessimism? Is this the unforgivable sin of admitting what everybody feels? Is it pessimism to diagnose cancer as cancer? Or should one simply go on pretending that everything is getting better everyday, because the time of the end is also – for some at any rate – the time of great prosperity? (“The Kings of the earth have joined in her idolatry and the traders of the earth have grown rich from her excessive luxury.” Revelations 18:3)”

The author Marc Ellis in his powerful biography of Peter Maurin (“Peter Maurin: Prophet in the Twentieth Century”, 1981), the French Catholic Anarchist, the teacher of Dorothy Day, and co-founder of the Catholic Worker movement writes: “Progress…is haunted by the cries of the dead and by those hundreds of millions who are separated from the structures that provide legitimation and affluence for the international elite but alienation and affliction for the majority of humankind.” Some of those so alienated and afflicted live here in greater Seattle.

Ellis states that the Hebrew prophets “were profoundly critical of contemporary values and social constructs that denied God’s covenant with his people. It was the general treatment of the poor and the oppressed that provided insight into the neglect of the covenant. Thus the prophets spoke and indeed came for those who were suffering. Their message was reflected broadly throughout the society, for the afflicted were signposts of the corruption of the affluent in the profanation of profit-centered business, the refusal to infuse values into commercial and social institutions, and resistance to serving the common good. However, it would be a mistake to see the prophets as social reformers. In the midst of judging human affairs, their task was to bring the world into divine focus and to unfold a divine plan. The rearrangement of social conditions was seen as a return to the correct ordering of the covenant and fidelity to God. Thus in the act of proclaiming judgment the prophet made known the beginnings of a religious movement toward salvation.”

More recently, the sociologist and soup kitchen volunteer William DiFazio has written: “The poor cause discomfort because they are indicators of the failure of capitalism” and that “the poor are continuously punished because in a global world where American capitalism is dominant, the poor are the indicators of the limits of the free market.”

Bringing about truly just and structural economic change in the Untied States is a risky and dangerous endeavor. In 1968, exactly one year after he came out against the Vietnam War, Martin Luther King, Jr. was gunned down in Memphis. At that time Martin was exhausted, frustrated, but still deeply committed to the Gospel call to fairness, freedom, racial parity, and economic justice in a land that he believed still held promise for the poor and outcast here, and that could still be beacon of hope to the wretched of the earth. Martin saw clearly the alarming contradiction contained in policies that pursued the lunacy of war yet purported a concern for domestic needs. In prophetic fashion, Martin saw through the madness, and in the course of his nonviolent efforts, he paid with his life.

At the time, Martin was steeped in the Poor Peoples’ Campaign, a visionary effort to bring fundamental economic change by organizing a massive movement of America’s dispossessed. He hoped to bring this economic justice movement into conjunction with the then formidable anti-war movement. Martin’s assassination ensured that this confluence did not happen. Indeed, in 1999, a civil trial held in Memphis resulted in a jury’s consensus that Martin had been killed with the collusion of forces of our own government. Yes, anyone who brings real concrete economic justice to the surface of our polity threatens the powers and principalities, and walks a most precarious and truly prophetic line.

After he had won the Noble Peace Prize, Martin had become a global human rights leader. In that capacity, Martin talked about homelessness – specifically homelessness in Asia. Martin was profoundly aware of economic disparities in America, but the notion of widespread systemic homelessness was still a phenomenon associated with the Third World. Yes, a few decades ago, the notion that widespread systemic homelessness could affect the lives of millions of American citizens would have seemed preposterous. Martin said: “More than a million people sleep on the sidewalks of Bombay every night; more than half a million sleep on the sidewalks of Calcutta every night. They have no homes to go into. They have no beds to sleep in. As I beheld their conditions, something within me cried out: ‘Can we in America stand idly by and not be concerned?’ And the answer came: ‘Oh no!’”

Today tens of millions of Americans suffer economic ostracism and fill the homeless shelters and jails. Many others live on the streets of cities large and small. Martin’s worst fears for this nation are being realized. Indeed the sermon he would have given the Sunday following his assassination was entitled “Why America May Go to Hell”.

A famous study of poverty in the United States is that of the late Michael Harrington’s great work “The Other America”. Published at the end of the 1950’s, the book detailed the topography of indigence at a time when many citizens mistakenly assumed that hard core poverty was no longer an issue in this materially rich nation. The book helped to launch the Kennedy/Johnson administration’s War on Poverty, which sadly floundered on the shores of Vietnam. However, it is instructive to realize that nowhere in Harrington’s study does he mention homelessness. This was due to the fact that only a few decades ago the problem of large scale systemic homelessness was not a part of the American landscape.

Twenty five years later, in “The New American Poverty” (1985), Harrington made explicit note of the significant numbers of homeless persons who had become a pervasive part of New York City’s urban terrain. Harrington recalled how in the early 1950s, when he was working side by side with Dorothy Day at the Catholic Worker, a few profoundly troubled people might become homeless and be taken in by the Catholic Worker or some similar operation. Most of the Bowery denizens back then found affordable shelter in the neighborhood’s numerous flop houses and cheap hotels. By the eighties, shifting economic policies at the national and municipal level precipitated rampant homelessness in New York. The dwindling traditional supply of modest Bowery housing finally gave out completely a few years ago when the last of the old-time “cage” SRO’s closed its doors. We are all well aware that a similar pattern unfolded in Seattle.

In his last book, “Socialism, Past and Future” (1992), Harrington wrote: “The great scandal of the late twentieth century – which has the terrible promise of persisting into the twenty-first – is still the structured inequality of planet earth.” It is in this regard that our city of Seattle gets mentioned in Mike Davis’s new and disturbing work entitled “Planet of Slums” (2006). He states: “If UN data are accurate, the household per-capita income differential between a rich city like Seattle and a very poor city like Ibadan [in Nigeria] is as great as 739 to 1 – an incredible inequality.” Of course, this planetary disparity has its own local manifestation within the midst of our region.

If we are to honestly appraise the disaster of homelessness and impoverishment in our midst we must confront a challenging reality: namely it is our very economic and political system epitomized by the increasingly unrestricted operation of market forces – the same system that has historically caused so much pain, penury, and dislocation in the Third World – that is now largely responsible for the desperate plight of growing numbers of citizens.

In his moving work entitled “Tell Them Who I Am, The Lives of Homeless Women” (1993), the late sociologist Elliot Liebow wrote: “Unemployment, underemployment, and substandard wages are system failures only when viewed from the bottom. Looking from the top down, they are seen as ‘natural’ processes essential to the healthy functioning of a self-correcting market system. From that perspective, it is as if the market system requires human sacrifice for its good health.”

In light of Liebow’s notion of the poor as sacrificial victims, consider this comment by the liberation theologian Gustavo Gutierrez: “Idolatry in the Bible is a risk for every believer. Idolatry means trusting in something or in someone who is not God…Very often we offer victims to [this] idol, and for that reason the prophets make a close connection between idolatry and murder.”

Christianity itself can assume idolatrous dimensions and has done so in contemporary America. Consider this comment by the Republican Louisiana congressman Richard Baker on the devastation of Hurricane Katrina: “We finally cleaned up public housing in New Orleans. We couldn’t do it, but God did it.” This outrageous comment inspired Lewis Lapham - at the time the editor of Harper’s Magazine - to remark that Katrina was, according to Baker, “a divinely inspired slum-clearance project.”

Writing in the Nation, Naomi Klein stated that some have referred to the rebuilding of New Orleans as an exercise in ethnic cleansing. If Representative Baker had lost loved ones, property, or a lot of money, I doubt that he would interpret such personal misfortune in such a cruel, crude, and superficial religious fashion.

Theologians of liberation Jon Sobrino and Felix Wilfred state: “Suppressing truth with injustice is a primordial sin of humanity which leads to dehumanization.” They invoke the words of Isaiah (5.20) “Oh, you who call evil good and good evil, who call light darkness and darkness light.” Thus there are people in our midst today who celebrate the condo conversion craze that reaps impressive financial rewards for a select group while displacing increasing numbers of citizens of modest means.

In the gospel of Luke, the kingdom of God is a reality promised to the poor. “Hence,” write Sobrino and Wilfred, “the utopia of the human family as a united whole should place the poor at its center.”

The rich and the powerful of today - perhaps of all time - have no intention of placing the poor at the center of anything except a program that will, if not eradicate them, contain and palliate them. Historically in America, displaced people have been met with suspicion, xenophobia, and violence. During the world’s first truly international depression – from 1873 until 1878 – many U.S. authorities called for “mass arrests, workhouses, and chain gangs” as a means of dealing with homeless wanderers (“CitizenHobo” by Todd Depstino, 2003). In 1877, the Chicago Tribune advocated “putting strychnine or arsenic in the meat or other supplies furnished to tramps” as a warning to others. The dean of Yale’s law school, Francis Wayland said that the homeless and jobless man of that day was a “spectacle of a lazy, shiftless, sauntering or swaggering, ill-conditioned, irreclaimable, incorrigible, cowardly, utterly depraved savage.”

In our own time, consider this haughty comment from Walter Wriston (“Twilight of Sovereignty”, 1992), former president of City Bank pertaining to the marginalized poor: They “will have little at stake in the global [economy] and may come to hate it and those who participate in it as they realize that in all this talk they are rarely mentioned and then only as a social problem. All technological progress has created social problems, and the information revolution moving over the global network is no exception. New skills and new insights will be required to survive and prosper, and those who do not or cannot adapt will be left behind with all the social trauma that entails.”

A more Darwinian scenario was limned by Jacques Attali, an associate of the late French president Francois Mitterand (“Millennium, Winners and Losers in the Coming World Order”, 1992): “The big losers of the next millennium will be the inhabitants of the periphery [namely the poor who comprise well over one half of all humanity, some of whom are citizens of the First World] and the biosphere itself.”

Given current trends, states Attali, the poor will find little relief except for the escape that alcohol and drugs can provide: “Drugs are the nomadic substances of the millennial losers, of the excluded and the discarded. They provide a means of internal migration, a kind of perverse escape from a world that offers none.” Indeed, in the comprehensive history of narcotics (“The Pursuit of Oblivion, A Global History of Narcotics” 2002), author Richard Davenport-Hines writes: “The illicit drug business generates $400 billion in trade annually, according to recent United Nations estimates. That represents 8 per cent of all international trade. It is about the same percentage as tourism and the oil industry.” Just last week, the Millenium Project of the World Federation of the United Nations reported that last year world-wide organized crime generated revenues in excess of $2 trillion – twice all the military budgets in the world combined. Much of this gargantuan haul is due to the vast profits emanating from the narcotics trade.

Attali is, however, revolted by the prospect of a dehumanized and biologically degraded future. Interestingly enough for people of a religious persuasion, he states that in addition to pluralism and political tolerance, humanity will have to embrace a “profound sense of the sacred.” And contrary to the Olympian indifference of Wriston, Attali urges the need for both global economic standards rooted in democracy and the retention of healthy localized forms of government.

As people of faith we are called to a radical witness and to break the bounds of bureaucratic habituation and political vapidity which too often pass for realism and practicality. At the very least we are called to inconvenience ourselves in the cause of justice. I say ‘inconvenience’ because for many of us it is a conscious choice we make freely and within circumstances that are not coercive. Many of us here today - not all - but many of us have the luxury of giving time to charitable efforts, of freely contributing time and energy to vital social causes but only as we choose and on our own terms. We can choose exactly how much time we wish to give, and when we wish to give it. It is important to recognize that though all this is well-meaning, it is ultimately a piecemeal practice and will never bring about the in depth changes that must be manifested - in our city, region, state, nation and world – if we are to achieve any modicum of fairness, of social decency, of economic democracy and justice.

Once Daniel Berrigan – the great Jesuit poet and peace activist - was asked why the forces of social change and peace were so seemingly ineffectual in the United States? Berrigan responded that the answer was painfully simple, that the forces of greed and war were at work twenty four hours a day while the forces of peace and justice were, at best, at work only on a part time basis. The creation of a Theology of Liberation for the United States is sorely needed – a trenchant theology of hope that embodies the praxis of action and reflection with the poor and homeless always at the center of deliberations. A Theology of Liberation for greater Seattle and for America will require a sacrifice of our time and energy – a sacrifice that will demand more of our time and energy than many of us have been yet willing or perhaps able to make.

“Poverty is not just the problem of those who are poor. Understanding the sources and nature of poverty is in fact the basis for addressing some of the larger social problems of our day.” That is a quote from John Iceland which can be found in his book entitled “Poverty In America, A Handbook” (2006). He also states: “Changes in public investment depend on the amount of public support they muster.” Despite growing inequities, widespread and sustained activism for social change and economic restructuring is nowhere commensurate with those structural and political forces which are formidable obstacles to the manifestation of economic justice.

Indeed this is a repeated observation articulated by sociologist William DiFazio, a professor at St. John’s University in New York. In addition to his teaching and writing, DiFazio has been a mainstay at a soup kitchen run out of a Catholic Church in the middle of the impoverished and crime-ridden Bedford-Styvesant neighborhood. If you do nothing different with your time and politics as a result of this talk and the rest of this day’s proceedings, do pick up a copy of DiFazio’s important new book “Ordinary Poverty” (2006).

As for shelters, soup kitchens, and related programs which mitigate social misery, DiFazio says: “I would never argue that these services aren’t necessary, but the price of advocacy and organization building is that activism and movement building become a very low priority.” Good people who operate shelters, counsel the poor, and who provide shelters, health care and other critical services can get so wrapped up in the day-to-day operation and maintenance of their respective programs, a broader social and political perspective is easily submerged in myriad quotidian demands. Concrete political activism – informed and sustained action that might alter and transform unjust economic structures which are often at the root of much stress and turmoil for the poor and working class – is rarely, if ever, pursued. Thus, year after year, we grow resigned to the expanding immiseration of the poor and homeless in our midst – and consciously or unconsciously we adapt to it. DiFazio writes: “The hopelessness of the poor has become ordinary.”

Many decades ago, Dorothy Day’s teacher Peter Maurin said it was imperative that social workers become social revolutionaries. Likewise DiFazio states that advocates must become activists: “They must learn a new language of possibility, and they must make the simple struggles needed to build the base for a social movement that exists in the multiplicity of race, class, and gender.” We are nowhere near building such a broad and sustainable movement to end poverty and homelessness. Thus he discusses the smaller more contained sporadic efforts that are made in various localities which he calls “simple struggles”: “These struggles must be seen as forms of life, ongoing processes that continue over a lifetime and always have the intention of building powerful social movements. ‘Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness’ demands the end of poverty. This is the movement for the new millennium.”

On this note I urge everyone who took the time today to join in the proceedings of this important conference to enhance the efficacy of our own “simple struggles” which are now unfolding within the greater Seattle region. These local simple struggles need your time, energy, and support. Involvement in them moves one from the standpoint of advocacy to the invigorated and necessary stance of activism which learns the necessity of challenging and confronting local bastions of economic power and political indifference. Too often it is charity rather than economic justice which defines the lineaments of approaches to our own deepening social problems. The persistence of this insufficient ethic will only obfuscate the problems and ensure a band aid strategy of appeasement while essentially guaranteeing the perpetuation of poverty and homelessness.

The recent occupation of the Lora Lake Apartments in Burien is an especially pivotal event. Though the occupation and arrests that followed did not bring about any immediate results, the action was undertaken by mostly homeless persons from the two Tent Cities. The support that came from the broader community and the religious community in particular was a critical ingredient in their nonviolent direct action. We must continue to support poor and homeless activists who in the future undertake nonviolent direct action to preserve sorely needed housing and in the process assert their own agency and thereby generate an atmosphere conducive to real progress and genuine economic justice. As for the Lora Lake Apartments, the complex should at the very least be reopened for occupancy this upcoming winter.

Currently the unprecedented wave of condo conversions and spiraling rents is generating a deepening crisis, not only for the very poor and those already burdened by displacement and homelessness, but increasingly for working people whose incomes are not enough to compete in such a tumultuous market. Those who are supposedly involved in the King County Ten Year Plan to end homelessness – including persons affiliated with United Way, the Gates Foundation, the Downtown Seattle Association and other similarly monied and influential corporate entities and individuals – must examine to what degree they are directly complicit in the current whirlwind of displacement while publicly pronouncing a concern for ending homelessness. Given current trends in our region, the vaunted Ten Year Plan will turn out to be nothing more than a blueprint for managing, not curing, the human-made disaster that is homelessness. In this regard, I urge citizens here from Seattle to support City Councilman Tom Rasmussen’s amendments to the condo conversion law.

Those gathered here today should express their full support for the immediate adoption of a “Right of First Notice” (or First Refusal) Ordinance that will allow tenants the first opportunity to purchase an apartment building that is up for sale.

Another heated battle currently underway involves the 191 low income and affordable units which comprise Lock Vista in Ballard. The tenants of this facility have demonstrated their willingness to stand up and fight displacement. The City of Seattle and the Seattle Housing Authority must hear from you. Urge them to take action. Condo conversions make a mockery of the Ten Year Plan. We should not allow Lock Vista to be lost to market forces.

And it has lately been noted that 66 units of perfectly habitable housing in Discovery Park may be purchased by the City of Seattle for $11 million only to be torn down for open space. A recent editorial in the Seattle P-I has urged that the city reconsider this situation given the housing crunch that has so deleteriously affected thousands of working class citizens. If you don’t weigh in on this, and the other critical issues noted in this presentations, little will change. Your presence here today is a clear indicator that you do not tolerate any perpetuation of current trends which exacerbate homelessness. Informed action and a deepening involvement are demanded of all of us.

Rev. Rich Lang has for a number of years talked about the need for a Northwest version of the Highlander Center. Perhaps there are persons here today with the time, energy and desire to assist Lang in making such an ambitious and noble project a reality.

More broadly as an interfaith church community, we are urged – in the words of Ernesto Cortes, Jr. of the Industrial Areas Foundation – to manifest a radical imagination in which “the church has a far more prophetic and transformative role to play in the larger social order…” Furthermore Cortes avers: “It is imperative to challenge the established concentrations of power and wealth so that we can all have shared prosperity, and shalom, and justice at the gates of the city.”

In doing so we must listen to the poor themselves, and ultimately a deepened sense of common cause must be created and sustained. Impoverished citizens themselves must be encouraged and supported in their efforts to rise from the condition of being merely recipients of charity to becoming empowered agents of progressive social change. As William DiFazio has stated “…the poor have not [yet] created a social movement to end poverty, nor have advocates helped to create one. As long as this is true, their poverty is permanent.”

Let me conclude this presentation with the words of the late Michael Harrington: “When we join, in solidarity and not in noblesse oblige, with the poor, we will discover our own best selves…we will regain the vision of America.”

— delivered September 18, 2007, at the Seventh Annual Building the Political Will to End Homelessness Conference

Bibliography:Attali, Jacques,

Millennium: Winners and Losers in the Coming Order, 1992

Davenport-Hines, Richard, The Pursuit of Oblivion: A Global History of Narcotics, Norton, 2002

Davis, Mike,

Planet of Slums, Verso, 2006

Depastino, Todd,

Citizen Hobo: How a Century of Homelessness Shaped America, University of Chicago, 2003

DiFazio, William,

Ordinary Poverty: A Little Food and Cold Storage, Temple University Press, 2006

Ellis, Mark H,

Peter Maurin: Prophet of the Twenty-first Century, Paulist Press, 1981

Gutierrez, Gustavo,

A Theology of Liberation, Orbis, 1973

Harrington, Michael,

The Other America, Penguin Books, 1963

Harrington, Michael,

The New American Poverty, Henry Holt & Co., 1984

Harrington, Michael,

Socialism: Past and Future, Little Brown, 1989

Iceland, John,

Poverty in America: A Handbook, University of California, Berkeley, 2003

Liebow, Elliot,

Tell Them Who I Am, The Lives of Homeless Women, Free Press, 1993

Merton, Thomas,

Raids on the Unspeakable, New Directions, 1966

Sobrino, Jon & Felix Wilfred, eds.,

Globalization and Its Victims, London: SCM Press, 2001. (out of print).

Wriston, Walter,

Twilight of Sovereignty: How the Information Revolution is Transforming Our World, Scribner, 1992

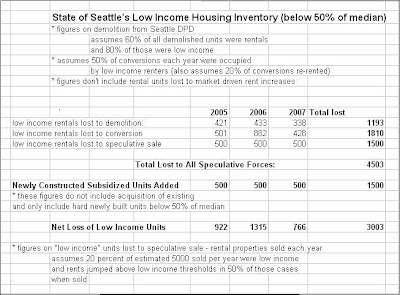

Lately, I've been wondering whether there really is, within this political universe, anything meaningful to be done about the widespread decline in housing affordability. Here in Seattle, as I've written before, the condo market is white hot, with tall skinny towers going up throughout the downtown and around 4,500 units of housing lost to condo conversions from 2005 to date.

Lately, I've been wondering whether there really is, within this political universe, anything meaningful to be done about the widespread decline in housing affordability. Here in Seattle, as I've written before, the condo market is white hot, with tall skinny towers going up throughout the downtown and around 4,500 units of housing lost to condo conversions from 2005 to date.